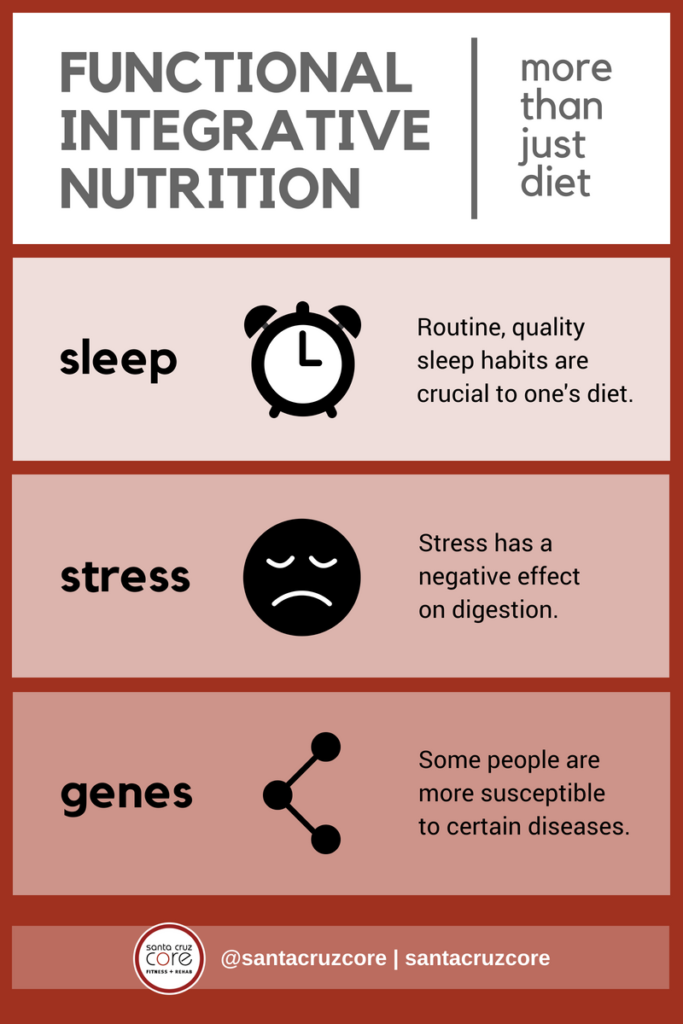

Diet is only one of the many aspects that define nutrition.

For this reason, Functional Integrative Nutrition (FIN) targets health status through more than diet alone. FIN takes many aspects into account including emotional state, daily activity, stress levels, sleep, genetic predispositions, and medical history on top of nutritional status. This helps paint a more complete picture of an individual’s health and allows for more targeted nutrition therapies. Additionally, the nutritionist or dietician determines whether a client needs to be referred to another professional more suited to help.

For this reason, Functional Integrative Nutrition (FIN) targets health status through more than diet alone. FIN takes many aspects into account including emotional state, daily activity, stress levels, sleep, genetic predispositions, and medical history on top of nutritional status. This helps paint a more complete picture of an individual’s health and allows for more targeted nutrition therapies. Additionally, the nutritionist or dietician determines whether a client needs to be referred to another professional more suited to help.

FIN combines knowledge of systems biology into its practice. Systems biology is a field of science that studies the complex interactions of biological systems and how these come together in an organism. By integrating systems biology into nutrition, a nutritionist or dietician can influence whole and individual body systems through targeted nutrition therapy.

It’s All Connected:

Each individual has a unique health status. This is because there are many variables playing a role in nutrition and lifestyle choices. Culture, for example, is one of them. Culture and food closely relate, many times defining the foods we habitually eat. The foods we frequent, in turn, reflect nutrient availability for the body and organ systems.

Many other aspects of life and of systems biology have an effect on nutrition. In this same manner, nutrition has an influence on aspects of life and of biological systems. Here are a few of the many aspects of health and body systems influenced by nutrition:

Sleep:

Sleep has a tremendous effect on daily energy levels and metabolism alike. Not sleeping enough or too much can negatively affect the circadian rhythm, energy levels, stress levels and hunger episodes.

Poor sleep habits can negatively affect hunger episodes via many hormonal pathways. Two of the most well-known hormones affected by detrimental sleeping habits are leptin and ghrelin. Leptin is a hormone that is made in relation to fat storages in the body; more fat equals more leptin. This hormone has an inhibitory effect on hunger, more leptin equals less hunger. Ghrelin, on the other hand, promotes hunger and is produced by cells lining the stomach.

Now, sleeping too much (>10 hrs) or too little (<5 hrs) for the average individual is associated with reduced leptin and increased ghrelin levels. What does this mean? It means that one is more likely to feel hungry throughout the day. We will have low levels of the hormone that controls hunger and high levels of the hormone that promotes it. This is only one of many ways in which sleep influences hunger and metabolism, but the opposite is also true.

Nutrition therapy can help promote sleep (when it is already a problem) and help regulate hunger episodes throughout the day. Foods rich in the amino acid tryptophan, for example, link to a promotion in sleepiness. This is because tryptophan is a precursor for serotonin, which can then converted to melatonin. Both melatonin and serotonin play a role in the onset and maintenance of a sleep. Additionally, by consuming foods which take longer to digest and with a low glycemic index, one can help control the timing of metabolic pathways and insulin release both of which influence the onset of a hunger episode.

Stress:

Stress has a negative effect on digestion. During acute-stress-response, much of the body’s blood flow directs towards the limbs and brain, supporting the fight-or-flight response. This means less blood flow for any ongoing digestion in the GI (gastrointestinal) tract as it is considered less crucial for the preservation of self. In severe cases of anxiety, nausea may result in vomiting.

Additionally, the release of glucocorticoids (stress molecules) from the stress response promotes gluconeogenesis (the formation of new glucose), increases glucose release from the liver, and stimulates the breakdown of fat. All of this increases the volume of energy molecules in circulation, fueling the stress response. At the same time, it contributes to unstable sugar levels and unstable moods.

Nutrition therapy can help cope with both stress and anxiety. Since anxiety, stress, and depression are troubles of the mind and mood, food which promotes a stable mood may help with coping. Alcohol and caffeine should be avoided, for example, as they affect heart-rate which is directly tied to both stress and anxiety. One could try to eat food with a low glycemic index as this will promote more stable blood sugar levels which in turn promotes a stable mood (1). Food rich in Omega- 3 fatty acids may also help improve mood and lower the incidences of cardiac arrhythmias (irregular heart rhythms).

Genes:

The field of FIN is unique in its ability to incorporate advanced biochemical principles into its understanding of human nutrition. The systems biology approach allows a nutritionist or dietitian to assess two new aspects of genetics known as nutrigenomics and nutrigenetics (2). Nutrigenomics refers to the interactions and interrelationships that exist between nutrients and gene expression. Nutrigenetics, on the other hand, focuses on a person’s genetic susceptibility to certain diseases.

Nutrigenetics has to do a lot with susceptibility to diseases. What does this mean? Well, certain individuals are more likely to develop medical conditions due to their heredity. For example, individuals of Native American descent are more susceptible to develop diabetes or become obese. This is partly because of their ancestral dietary habits and because of evolutionary adaptations developed to store more fat. Native American cultures relied a lot less than European cultures on the domestication of animals for food. Rather, they hunted and consumed large amounts of nuts and leaves. Why is this significant? Domesticated animals move a lot less. As a result, more fat is stored, which is then consumed by those who eat it. On the contrary, hunted animals are running wild and the meat they provide is a lot leaner than a domesticated farm animal.

Over time, small differences like this led to evolutionary adaptations in both types of individuals. Those of Native American descent are more likely to store animal fat, while those of European descent have metabolic adaptations to make more use of it. Now, this isn’t a solid a line, as genetic variation and its effect on metabolism is more complicated than that. But it helps to get an idea as to why or how we get different metabolic patterns.

Nutrigenomics takes this variation into account and then applies knowledge of the nutrient availability of organ-specific and tissue-specific function. This, in turn, has an effect on the cellular hallmarks and cues available for gene expression.

In the same way that each of these three aspects of health integrates with nutrition, there are many more to be accounted for. Inflammation, toxin exposure, medical history, chronic illness, and many others come together to define health and thus are a target of nutrition therapy. To get more info on how many life aspects come together to define your specific health status contact one of our Nutrition Consultants or Dietitians.

References:

Naidoo, Uma. “Nutritional Strategies to Ease Anxiety.” Harvard Health Blog, Harvard Medical School, 24 Mar. 2016, www.health.harvard.edu/blog/nutritional-strategies-to-ease-anxiety-201604139441.

Noland, Diana. Dietetics and Integrative Medicine: Curriculum Development Model. University of Kansas Medical Center, 2016.